The ten best films of … 1934

Saturday | January 11, 2025Story of Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu)

Kristin here:

This surprisingly popular series started with what we assumed to be a one-off entry. In 2007 David and I saluted the birth of the Classical Hollywood Cinema in 1917 as a full-fledged new set of norms that would last until the present day and influence filmmakers around the world. Introducing the list of ten films from ninety years earlier (for the list, click on the 1917 link below), David wrote:

This is the season when everybody makes a list of best pictures. We have stopped playing that game. For one thing, we haven’t seen all the films that deserve to be included. For another, the excellence of a film often dawns gradually, after you’ve had years to reflect on it. And critical tastes are as shifting as the sirocco. Never forget that in 1965 the Cannes palme d’or was won by The Knack . . . and How to Get It.

Still, enough time has elapsed to make us feel confident of this, our list of the best (surviving) films of 1917, both US and “foreign-language.”

That notion of time elapsing became the somewhat risible rationale for our series: surely ninety years is enough that one can be confident in one’s choices of old films worth watching and rewatching.

David ended that first entry, “Next year, maybe we’ll draw up our list for 1918.” This is our eighteenth such list. I took the initiative to follow up and have written all the entries–consulting with David each time, of course. This is my first time without his advice, though I know there are films on this new list with which he would have heartily agreed, others that he would agree are important enough to include, and one or two that he would be dubious about.

Previous lists can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1932, and 1933.

As in the past, I begin the process of choosing the ten films to included thinking that this year will be the one where there are ten obvious choices. During the transition to sound, the pickings have sometimes been slim, and in recent years I have filled in with one or two films that don’t quite stand up to the others in the final list. I had high hopes for 1934, but again I have had trouble deciding on a film to fill the final slot. As the 1930s progress, I am confident that it will be considerably easier to think of titles to make the list. Renoir will enter the height of his career, Mizoguchi’s films start surviving, Ozu maintains his high level until the war intervenes, and so on.

L’Atalante (Jean Vigo)

L’Atalante is surely one of the first films one would think of when asked to name great classics from 1934. Vigo made a couple of shorts, but his high reputation is based on only two films, Zéro de conduite and this one. Zéro was on my 1933 list. It’s a strange combination of surrealism, slapstick, magical realism, and bitter satire.

L’Atalante is none of these, really, but instead a poetic romance played out on a canal barge, the name of which gives the film its title. It begins just after the wedding of a young village woman, Juliette, and Jean, the captain of the barge. As they walk proudly toward the canal, the villagers follow them, muttering their disapproval at Juliette’s decision to marry an outsider with a strange profession. The pair are clearly much in love, but things begin to go wrong as Juliette gets bored with the monotonous routine aboard the barge. Once they arrive in Paris, there are quarrels, especially when Juliette responds naively to a handsome peddler who flirts outrageously with her. Juliette leaves to see the city, but in a fit of unjustified jealousy, Jean casts off, leaving her behind. The pair grow increasingly sad at their parting.

This slim plot is delightfully padded by Michel Simon as the eccentric Père Jules, Jean’s only adult crew member on L’Atalante. He drifts among moods, being funny, poignant and slightly menacing by turns. The antiques and gewgaws that he has collected in his long career of sailing around the world provide the few somewhat surrealistic touches that are more prominent in Zéro de conduite. These range from a sinister mechanical puppet of a music conductor to the rostrum of a large sawfish fastened to the side of a bed.

As often has been the case with the films on these lists, in my graduate-student days I saw L’Atalante in a low-contrast 16mm print. The restored version available on The Criterion Channel and in the Criterion Collection’s Blu-ray of Vigo’s complete oeuvre is a huge improvement.

Les Misérables (Raymond Bernard)

By contrast to Vigo, Raymond Bernard is not a name that comes readily to most people’s minds when one thinks of French cinema in the 1930s. He had gained a reputation for making epic historical films in the silent era, most notably The Miracle of the Wolves (1924), an impressive but already old-fashioned, rather stodgy tale of Fifteenth Century France. (Available online in a restored version subtitled in English.) In the early sound era, however, the success of those earlier films allowed him to make two masterpieces.

Wooden Crosses featured on my 1932 list. It was highly successful in France, giving Bernard the chance to immediately launch into an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s popular novel. He proposed making it in three feature films in order to retain as much of the story as possible: “Une tempête sous le crane,” “Les Thénardier,” and “Liberté, liberté chérie.” The tale intertwines two plotlines. Hardened criminal Jean Valjean escapes and reforms through the love for Cossette, an abused orphan he rescues from harsh innkeepers (the Thénardiers). He becomes respectable and rich under a false identity, though he is in constant danger from Inspector Javert, who implacably seeks for years to track him down. The second plotline deals with young people involved in the French Revolution, one of whom falls in love with the grown-up Cossette.

Harry Baur and Charles Vanel, playing Valjean and Javert respectively, are ideally cast. As in Wooden Crosses, the cinematography by Jules Kruger (who also shot Wooden Crosses and was one of several cinematographers on Napoléon vu par Abel Gance) is superb. Apart from the remarkably precise lighting (see above), it contains many shots using a canted framing, a technique that later drew considerable attention in The Third Man. Here Madame Thénardier scolds Cosette and a group of revolutionaries hold a meeting.

The three features made Les Misérables into a serial, much like Alberto Capellani’s 1912 version. Again, it was a considerable success. The film industry in France was in trouble as the Depression dragged on, however, and expensive epics like those of Bernard were no longer feasible. He was assigned to lower budget films, including romantic comedies, while other directors introduced the Poetic Realism that characterized the rest of the decade.

Les Misérables‘ popularity led to its being re-released repeatedly with various re-edited, shorter versions playing for decade, starting in 1935. In May Pathé released a two-and-a-half-hour version, eliminating about half the original film’s length. This and other versions are summarized in Criterion’s notes to the Eclipse set. Late in his life Bernard was able to help assemble footage from several prints, leading to a restoration that still lacks a few scenes.

Les Misérables is available on The Criterion Channel and from The Criterion Collection in the same Eclipse box set that contains Wooden Crosses. Arthur Honegger’s very effective score for the film has been released on CD and is still in print.

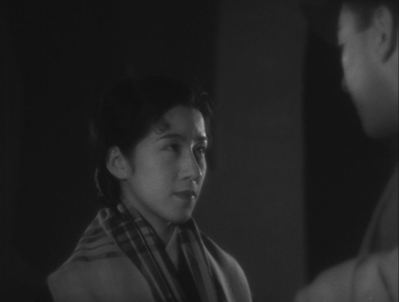

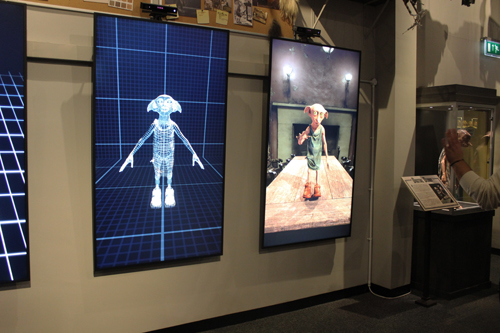

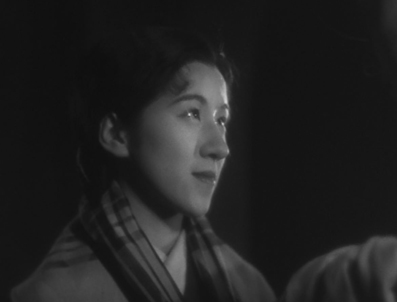

Story of Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu)

The last four years’ best lists have included films by Ozu: That Night’s Wife (1930), Tokyo Chorus (1931), I Was Born, But … (1932), and a double-header, Passing Fancy and Dragnet Girl (1933). For 1934, he’s back with Story of Floating Weeds. (His other film of that year, A Mother Should Be Loved, unfortunately is missing the first and last of its nine reels.)

The story revolves around a down-at-heels traveling theatrical troupe which stops to performs in a rural village. They remain there for longer than the dwindling audiences would warrant, and we learn that the group’s leader, Kihachi, is secretly visiting an old flame of his and their son, Shinkichi. She has raised the boy to believe that his father died long ago. He thinks that Kihachi is his genial uncle. The female lead in the company, Otaka, who is also Kihachi’s mistress, learns of this. Out of jealousy she enlists a younger actress, Otoki, to seduce the boy, thus threatening his promising future.

As David points out in his Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, this film departs from Ozu’s earlier work:

The film is played in a remote rural village, a realistic locale for the traveling troupe but an unusual setting for Ozu at this point in his career. The cinéaste of urban Tokyo, of nansensu [nonsense] and moga [modern girl], must now impose his narrational system on a different Japanese iconography: the village street, the landscape, the forlorn café, the decaying theatre. He must film a traditional, if ineptly staged, performance. He must no longer cut away to Lincolns or spinning ventilators or Nipper the RCA dog. Ozu now experiments with treating centuries-old material in his own, recently matured manner. (p. 257)

One example of village iconography that he cites is the “death tree,” a folk tradition where small memorial banners are left for the dead. Otoki sits by the tree as she waits to seduce Shinkichi, and “her casual intrusion into a sacred space underlines the extent to which the actress is an outside to the village” (p. 258). By contrast, the scene in which Kihachi goes fishing with his son uses the countryside to indicate a mood of natural serenity.

Story of Floating Weeds is not bereft of the humor present in so many early Ozu films, but he largely confines it to the early scenes, before we learn of Kihachi’s secret life. The inept theatrical performance includes people in obvious animal costumes, as when the young boy of the troupe plays a dog, standing up, taking off its head, and scratching his crotch (top) while Kihachi tries to remain in character. Later, when it starts to rain, water comes through the numerous holes in the roof, and the actors pass through the audience, who are seated on the floor, passing out bowls to catch the drips. Once this early portion of the film is over, the tone turns toward melodrama, and there are only rare moments of humor.

Story of Floating Weeds, along with many of Ozu’s films, is streaming on The Criterion Channel and is available as a DVD or Blu-ray in Criterion’s box set pairing it with Ozu’s 1959 remake, Floating Weeds.

Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks)

Hawks was one of those rare Hollywood directors who could work in virtually any major genre and make outstanding films. He made gangster films, musicals, westerns, murder mysteries, romances, comedies, and military films. He also dabbled in less fruitful genres: science-fiction (assuming he really directed The Thing from Another World) and historical epics (Land of the Pharaohs).

The first film that comes to mind when contemplating Hawks’s comedies is no doubt His Girl Friday. One of David’s and my favorite Hollywood films, it featured in at least two recent film series compiled as tributes to him (the UW Cinematheque last summer and The Music Box in Chicago in September). Next would probably be Bringing Up Baby. Maybe I’m wrong, but I suspect Twentieth Century would come in a somewhat distant third. Yet it is, to put it mildly, hilarious, with a great script and two outstanding central performances backed up by some of the great character actors of the period.

Although John Barrymore started out on the stage with light comedies, he soon was starring in Shakespeare, including his Hamlet, which led to him being dubbed “The greatest living American tragedian.” Once he moved into films in the 1920s, he usually was cast as the lead in prestigious literary adaptations and romances: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Sherlock Holmes, Beau Brummel, Beloved Rogue, Don Juan, and perhaps Lubitsch’s least interesting silent film, Eternal Love. The pattern continued into the early sound period, most notably in Grand Hotel.

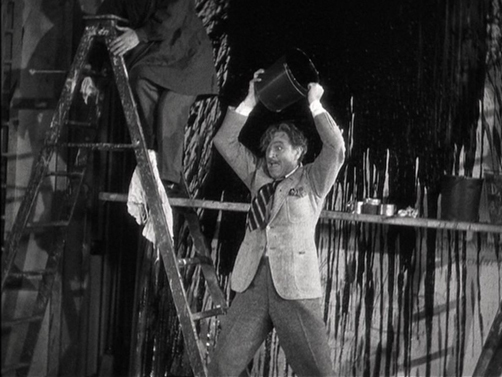

Hawks gave him the chance to cut loose his comedic talents, and the resulting performance was flamboyant. To say Barrymore overacted is a mistake, I think, since theatrical impresario Oscar Jaffe is a ludicrously flamboyant character.

The film starts with Jaffe transforming a lingerie model into a theatrical star, Lily Garland (Carol Lombard, who became a major star with this film). They begin a tempestuous affair. Years later, realizing that Jaffe is jealously watching her every move, she flees to Hollywood and becomes a movie star. Without her, Jaffe’s plays fail, and he heads for Los Angeles to beg her to return. Coincidentally they end up on the same train without initially being aware of it, and their battles resume.

The departure of Lily for Hollywood removes Lombard from the action for a lengthy period, giving Barrymore a chance to demonstrate that he can do comedy with the best of them. Upon learning that Lily has left him, Jaffe staggers through the theater, ranting as his mercurial moods swing from despair (“Let life run over me!”) to rage (“Anathema! Child of Satan!”):

Once the pair meet on the Twentieth Century, Lily refuses to return to Jaffe, and an shouting match begins. This ends with the two collapsing in utter exhaustion (top of this section). Lombard holds her own through this, but she is the more sensible of the two and generally acts with more restraint in other scenes.

There is a very funny running gag about an innocent-looking elderly man who surreptitiously posts stickers reading “Repent for the time is at hand,” and Walter Connolly and Roscoe Karns, playing Jaffe’s assistant, provide wisecracks as Jaffe repeatedly hires and fires them.

Twentieth Century can be streamed on Amazon Prime and Apple + for $3.99. A fairly decent DVD is available.

The Man Who Knew too Much (Alfred Hitchcock)

Like Twentieth Century in Hawks’s career in the 1930s, The Man Who Knew too Much is one of the underrated films of Hitchcock’s career in this period. David and I both liked it very much. Indeed, when he was starting out teaching Introduction to Film at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he showed it to the class. A brief essay about it featured in the first edition of Film Art: An Introduction in the “sample analyses” section. (This was and still is intended to demonstrate how to analyze form and style across an entire film rather than just learn about individual film techniques.) We replaced it after the second edition with a different analysis, but like all the other sample analyses that have been replaced during revisions, it is available on David’s main blog page. Click here and scroll to the bottom of the list to download a PDF of it.

The brief description there says:

Like His Girl Friday, The Man Who Knew Too Much presents us with a model of narrative construction. Its plot composition and its motivations for action contribute to making the film what a scriptwriter would call “tight.” Moreover, the film also offers an object lesson in the use of cinematic style for narrative purposes. Finally, the film illustrates how narration can manipulate the audience’s knowledge, sometimes making drastic shifts from moment to moment.

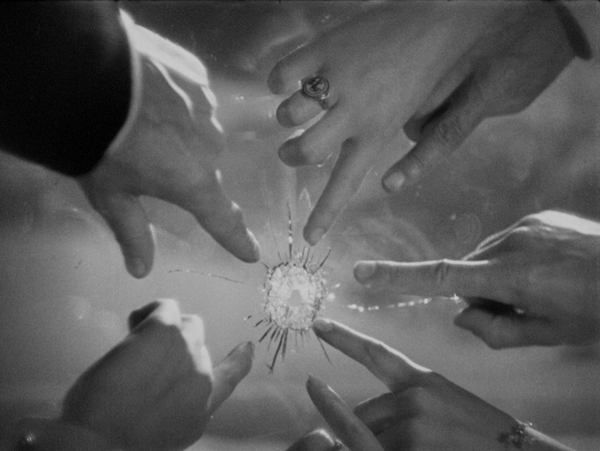

We both considered it superior to Hitchcock’s 1956 remake. After all, it is indeed “tight,” telling the entire story in a mere 75 minutes as opposed to two hours. And Hitchcock is increasingly adept at telling his story visually. Take the striking image above. The second scene at a fancy hotel restaurant involves the assassination of Louis Bernard, a friend of the Lawrence family, who are unaware that he is a French spy cooperating with British intelligence. The shot comes from offscreen, and we watch Bernard die in the midst of a crowd. Hitchcock doesn’t have anyone tell us that the bullet came from outside. He cuts to a shot of the star-shaped hole in a window with five people pointing at it, their fingers extending the star-shaped pattern of the cracks. (Never mind that a vertical window could not be pointed at from all sides.)

The casting is also better, in my opinion. (I like Doris Day well enough, but when I watch her, I want it to be as Babe in The Pajama Game.) Lesley Banks makes a good protagonist. His attempts to ingratiate the main villain, Abbott, by acting nonchalant and amused by his banter, even though he knows this man has kidnapped his daughter and is holding her in a room nearby. Abbott is played by Peter Lorre, who is a major asset in the film. (David always claimed that Lorre improved any film he was in, which is quite possible.) On the right below, Abbott calmly has a meal, contrasting with all the other characters, who tensely listen to the radio, waiting for the climactic moment in the orchestral piece when the second assassination is planned to happen.

Back when David was teaching the film, prints were gray and fuzzy. Luckily the Criterion Blu-ray features the restored version, and it is playing permanently on the Criterion Channel as well.

The Merry Widow (Ernst Lubitsch)

I am not particularly fond of Lubitsch’s musicals from the 1929-1932 period. Hence I had never made much effort to see the slightly later The Merry Widow, in part because it’s not that easy to see, as I’ll explain below.

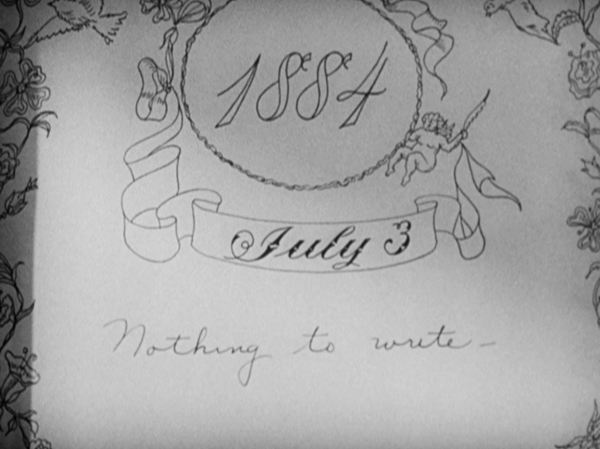

The story begins in Marshovia, a tiny imaginary kingdom in eastern Europe. The opening number introduces Captain Danilo (Maurice Chevalier), who has apparently bedded most of the female population of the country. He is intrigued by the mysterious black-garbed widow, Madame Sonia, who is so wealthy that the economy of the country depends largely on her. He invades her home in an attempted seduction, but in a bantering exchange Sonia rejects him. That her mourning is oppressing her is conveyed by pages of her diary turning, with shorter entries culminating with “Nothing to write-” (above) followed by blank pages.

Determining to live an exciting life, she departs to Paris. Danilo is dispatched to woo and marry her so that she will return to Marshovia. Though initially he tries to seduce her, but naturally he falls in love with her. She, aware of his reputation, dismisses his wooing as lies and continues her madcap life.

With such a risqué story to tell, Lubitsch manages to convey it with visuals and innuendos. Sonia’s sudden transition from mourning widow to reckless, fun-seeking widow is handled by a series of dissolves which show her black shoes, dresses, hats, and even corsets turn white (at least in a black-and-white film).

When she asks her three maids where Danilo lives, all three cheerily reel off the same address address. Realizing what they have revealed about their relationships with the serial seducer, their smiles disappear as they lower their eyes–the Lubitsch Touch at work.

The use of Franz Lehar’s music (though with some altered lyrics) leads to a better quality of musical numbers than most films of the day had. Lubitsch was also given a considerable budget, and the set design won Oscars for Cedric Gibbons and Frederic Hope.

The two leads are inevitably charming, and once again supporting players–Edward Everett Horton, Una Merkel, Donald Meek, and Herman Bing–supply humor throughout.

The Merry Widow is streaming on Amazon Prime and Apple +, with a $3.99 rental charge. It unfortunately is not in the Criterion Collection’s box set of Lubitsch musicals, but is available on a Warner Bros. Archive DVD.

It Happened One Night (Frank Capra)

I doubt I need to say much about this one. Anyone who hasn’t seen it probably is not interested in seeing ninety-year-old films and certainly wouldn’t be reading about them here.

The plot is known to all. Ellie Andrews, the spoiled child of a doting, wealthy father flees to rejoin her new husband, whom she thinks she loves. He wants the marriage annulled, assuming the man is after her money. On a bus from Florida to New York, she meets Peter Warne, a newspaper reporter in trouble with his boss. They take an instant dislike to each other, but Peter offers to take care of Ellie if she will give him an exclusive story about her flight. They encounter numerous problems, from stolen luggage to a steadily dwindling supply of cash.

The casting of Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert is perfect, the script is great, etc.

Again, this is a film I saw back in my graduate-school days. I enjoyed it, but it was the typical soft, low-contrast 16mm print so common in those days. The 4K restoration on the Criterion Blu-ray reveals something that was not evident then: this film was superbly lensed by the great cinematographer Joseph Walker, who shot many of the screwball comedies of the decade but also the brooding Only Angels Have Wings. The scene of the two forced to sleep rough on some improvised hay beds is as good as a three-point lighting in a night-time, studio-shot set can get. There’s also the simpler scene which holds on Ellie in silhouette, having a conversation with Peter across the blanket serving as “the Walls of Jericho.”

It Happened One Night is probably not the first screwball comedy, which is considered a sub-genre of the romantic comedy. It may be the first in what I think might be a sub-sub-genre, which revolves around a rich woman who can afford to follow her whims and defy conventions. Ellie starts out rich, though her money is stolen during early on. Carol Lombard’s character in My Man Godfrey is another classic case, with a carefree young woman from a wealthy family finds a homeless man as required for a scavenger hunt, paying $5 for him to appear at a party. His indignation leads her to hire him as a butler. Bringing Up Baby also depends on the Katherine Hepburn character’s wealth that allows her to follow her whims and boss Cary Grant’s paleontologist around. In all cases the man resists being manipulated, but love results eventually.

It Happened One Night is available in an excellent restoration on Blu-ray and DVD from Criterion. It streams on Apple + and some smaller services for $3.99.

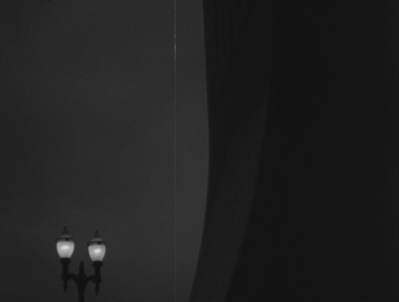

Street without End (Mikio Naruse)

Naruse is known to many from his prolific career after World War II. In the 1930s, however, he also made many films, though a considerable number of those are lost. He was one of the four major directors working for Shochiku, the others being Yasujiro Ozu, Hiroshi Shimizu, and Heinosuke Gosho. The head of the studio, however, did not consider him to be on the same level as those three, and Naruse felt that he was being given less creative freedom than the others. Indeed, the other three had passed on the script for Street without End, since it was based on a tabloid serial about a café hostess. Naruse had no choice but to accept the assignment.

Naruse frequently centering his plots around women. In this case, the protagonist is Sugiko, a working-class woman content with her job in a café. She is approached by an film-studio agent who offers her an acting job, but despite her waitress friend Kesako’s excitement at the idea, she turns it down. Kesako takes the job instead and is a success but grows tired of the job. Sugiko is slightly injured struck by a car belonging to a rich man, Hiroshi, a man from the upper-class Yamanouchi family. He falls in love with her and proposes. All her friends urge her to jump at this chance, but her brother warns her that the wealthy family will not accept her. Despite this, Sugiko loves Hiroshi and marries him. As predicted, Hiroshi’s mother and sister snub Sugiko and make her married life miserable.

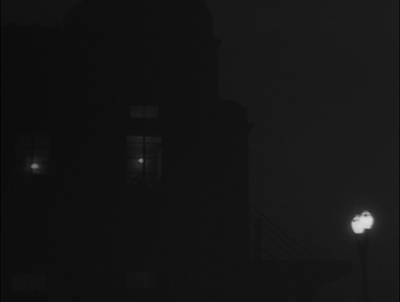

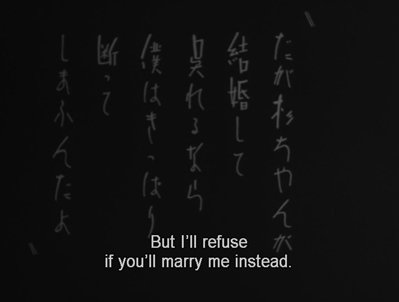

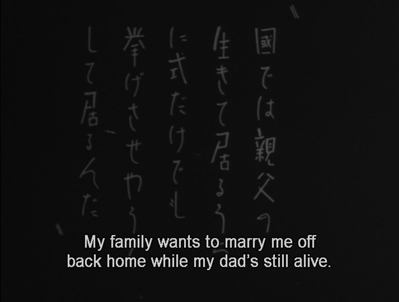

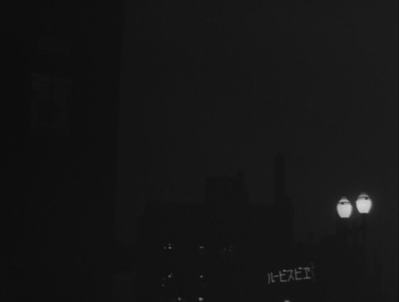

Naruse’s style in the film somewhat echoes that of Ozu, yet he seems to be trying variants on it. In this early scene, Sugiko’s boyfriend Machio breaks the news that his family has found a bride for him, but he says he’ll marry Sugiko if she agrees. In the course of the scene, Naruse cuts away from the couple to shots of two street lamps, seen from a different angle each time. Ozu typically uses shot of spaces without the characters as a transition device between scenes, but here such shots interrupt the action repeatedly.

1 2

2 3

3

7 8

8 9

9

10 11

11 12

12

Once Machio has said he will marry Sugiko, there is another shot of the two lamps, closer than before (11). This is followed by a shot/reverse shot pattern between the two. At first Machio is seen looking rightward (12), with the cut to Sugiko showing her also facing rightward (13), a common tactic used by Ozu. Here, however, the cut back to Machio shows him facing leftward (14), as would be conventional following a shot of her looking rightward. Ozu would keep the characters facing the same direction throughout a shot/reverse-shot pattern (shots 9, 10, and 11). In shot 11 Machio turns to exit and shot, and in 15 he is seen from behind walking away from her–perhaps because she does not answer him immediately.

13 14

14 15

15

The only reason I can see for this change on the framing of Machio in the second shot of him is an echo of an earlier moment in the scene. In the shot in which Sugiko reacts to his news of his parents plan for him to marry, she turns away and starts out left (frames 6 & 7 above). The next shot shows her from the back, moving away from him. Within this shot, he goes after her and faces her again (frames 7 and 8). A cut-in leads to the inconsistent shot/reverse shots. This time he is the one to move away from her (compare frame 15 with frame 8). He returns to say they will have little money (16). After another cutaway to the two lamps (18), the scene continues with Sugiko saying will marry him anyway. Perhaps this echo hints at their eventual failure to marry.

16 17

17 18

18

Through this sad main plotline Naruse weaves some lighter scenes involving Kesako. Her boyfriend is a move comic figure. A running joke compares his rather sloppy “modern” painting with a close view of him carefully setting up an elegant stack of apples and other objects as a model. In later scenes he shows off the painting and has to inform people that the subject is indeed apples.

As the title suggests, most of the action takes place in Tokyo and specifically the Ginza district. Sugiko’s romance with the weathy Hiroshi takes place in the countryside, emphasizing that he has an expensive car and can take her on such trips (top of this section). One might assume that this lyrical scene featuring Mount Fuji refers to Shochiku’s famous logo, but that logo was not adopted until 1936.

Street without End was Naruse’s last film for Shochiku. He left for the Photo-Chemical Laboratories studio, late to become Toho. His first film there remains his best-known from the era, Wife, Be like a Rose! (1935).

Street without End is one of five films from the first half of the 1930s in the Eclipse box set, “Silent Naruse.” It also streams on the Criterion Channel.

Dos Monjes (“Two Monks,” Juan Bustillo Oro)

As usual, I like to include an excellent film that deserves to be far better known. I first saw Two Monks at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in 2017. For me the most unexpected discovery of the festival. The occasion was a restoration of the film by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. I was impressed and blogged about it at the time. Here is a slightly revised version of what I wrote then.

It is considered the first in the Mexican Gothic genre. It was inspired by the Spanish-language version of Dracula (directed in 1931 by George Melford for Universal), as well as by German Expressionist films. Yet there are no monsters or supernatural villains in the film. Instead, a frame story set in a monastery that looks straight out of Murnau’s Faust (1926) introduces a young monk, Javier, who has gone mad. He attacks another monk, Juan, with an expressionistic crucifix and confesses to the prior that he did so because Juan had committed a terrible crime.

A lengthy flashback lays out the story of Javier’s love for Ana and his eventual rivalry with Juan. In the second half, Juan also confesses, and the story is repeated from his point of view. Scenes we saw earlier are replayed, often starting at an earlier point or ending at a later one, in a way that alters our understanding of the two monks’ past relationship. The result is not a Rashomon-type situation, for the two men agree on the events they describe, disagreeing only on the implications of those events.

It’s a remarkable narrational technique for this early in film history. The atmospheric claustrophobia created by the small cast (no passers-by are seen in the brief street scenes and no servants appear in the houses) and of dread created by the sets and the dissonant music of the climactic scene would bear comparison with the horror films of Universal and Hammer.

Two Monks is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel and some other platforms. It is available as a Blu-ray in the third of the multiple-film releases from the World Cinema Project, along with Héctob Babenco’s Pixote and also in a larger box set with six films.

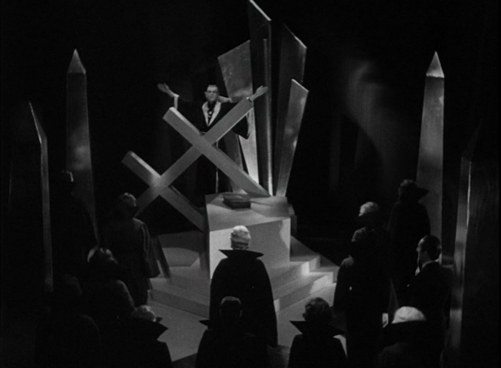

The Black Cat (Edgar G. Ulmer)

I must admit that I spent quite a bit of time trying to decide on my tenth film, which in part caused this annual post to be a little late. I settled on Edgar G. Ulmer’s only contribution to the considerable number of Universal horror films of the 1930s. I’m not particularly a horror fan, but The Black Cat is my favorite of the Universal series. It has some characteristics that set it apart from the others.

One of these characteristics is that it doesn’t depend on some sort of science-fiction (Frankenstein) or supernatural (The Mummy and Dracula) monster. This makes it similar to James Whale’s The Old Dark House, my other favorite of the series. Instead The Black Cat concerns atrocities committed during World War I in a fictitious fort at Maramureș.

The plot of The Black Cat has one parallel to The Old Dark House. Both begin by introducing a couple who are forced by an accident caused by a storm to seek shelter in an an isolated house. In The Black Cat, newlyweds Peter and Joan Allison meet the kindly Dr. Vitus Werdegast (Bela Legosi), who helps them when the accident occurs and takes them to the house of his old nemesis, Hjalmar Poelzig (Boris Karloff). Poelzig traitorously surrendered the fort during the war, causing huge casualties. He now secretly performs Satanic rituals. After fighting in the war, Werdegast has spent fifteen years in a Siberian prison camp and now wants to find out from Poelzig what happened to his wife and daughter. Unbeknownst to him, Poelzig had married his wife and then, after her death, their daughter Karin.

Another thing that sets The Black Cat apart is that its setting is quite the opposite of the conventional old-dark house. Poelzig has designed his own house, a modernist, vaguely art deco mansion located atop the fort, which contains what Werdegast describes as 10,000 corpses of war victims.

To be sure, once Poelzig’s full madness is revealed, the action moves to the dark rooms below the house. One corridor contains cases holding corpses of women whom he hass somehow preserved, including Werdegast’s wife. An expressionistic set where he holds the Satanic rituals, including human sacrifices.

These settings add to the beauty of the film, a beauty uncommon in the Universal horror films. The other part of that look is accomplished by the cinematographer John J. Mescall. Mescall lensed a huge number of films during his career, most of them minor works. His main other claims to fame were King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924); two Lubitsch films, So This Is Paris (1926) and The Student Prince in Old Heidelburg (1927); Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935); and John M. Stahl’s Magnificent Obsession (1935). The first look at Poelzig in the film comes when he wakes up and turns on the bedside light, creating a dramatic and ominous composition (above).

The Black Cat is noted as the first film that Karloff and Legosi starred in together. The contemporary setting and lack of supernatural elements allows both of them to act with less heavy make-up than usual. Legosi plays the rational and kindly (until the end at least) Werdegast impressively, which is a novelty. Similarly, as Poelzig, Karloff hides his villainy with cordial, polite conversation until the climactic ending.

6

6